Topic(s): Delinquent Tax Enforcement

In Honor of Tax Day: A Crash Course in Tax Foreclosure Reform 101

April 15, 2014

In the midst of flurries of W-2s and fingers crossed for refunds, we’re taking the opportunity on this Tax Day to break down a different tax-related challenge: delinquent property tax foreclosure reform. It’s a mouthful, and it can be complex, but tax foreclosure systems have a big impact on the fight to reclaim blighted, vacant properties.

So if you’ve had your fill of E-Filing for this year, keep on reading to learn a bit more about the connection between tax foreclosure reform and neighborhood revitalization.

In the video below, State Representative Chris Ross (158th Legislative District – Pennsylvania), speaks with us about the challenges tax delinquency creates for communities and what reform could achieve. We here at Community Progress then dive deeper to answer some common questions.

By the end of this mini crash course in Tax Foreclosure Reform, you’ll understand what delinquent property tax enforcement is, why it matters, and how systems can be improved to help communities revitalize.

Tax Foreclosure Reform 101

What is delinquent property tax enforcement?

Property taxes supply local government with the revenue to provide essential services. Any loss in this revenue, whether from decreased property values or from nonpayment of taxes, directly impacts local government’s ability to provide these services. All states have systems in place that enable local governments to enforce the payment of delinquent taxes or, where the initial enforcement process fails, to force the transfer of property ownership — a process called tax foreclosure. Enforcement processes vary by state and sometimes by municipality, and are complex. Because each delinquent property tax bill represents a loss of public revenue and relates to a particular parcel in a particular community, the existence of an efficient, effective, and equitable delinquent property tax enforcement system is critical to support municipal budgets and to ensure neighborhood stability.

How is property tax delinquency related to neighborhood stabilization?

A property owner’s decision to stop paying taxes is frequently, though not always, a sign that the owner plans no further investment in the property. This is most commonly the case with commercial, retail, industrial, or residential rental properties. It is less likely the case with respect to owner-occupied residential properties, unless data also indicate a correlation with mortgage foreclosures in a concentrated neighborhood.

A property owner’s decision to stop paying taxes is frequently, though not always, a sign that the owner plans no further investment in the property. This is most commonly the case with commercial, retail, industrial, or residential rental properties. It is less likely the case with respect to owner-occupied residential properties, unless data also indicate a correlation with mortgage foreclosures in a concentrated neighborhood.

An increase in tax delinquency results in a direct decline in government revenues, which strains the resources available for local government to provide services, including services that address the consequences of property abandonment. As a result, a cycle of nonpayment of property taxes can become a spiral of deterioration.

In far too many jurisdictions, property tax delinquency marks the beginning of a complex and prolonged period of enforcement through tax foreclosure. Tax delinquent properties have higher rates of vacancy and are more likely to have outstanding code violations and to generate a higher frequency of calls to the police. When a community’s tax enforcement process is inefficient and ineffective, tax delinquent properties can sit vacant for many years, harming the value and safety of surrounding properties and contributing to blight.

What are the fiscal and community impacts of the sale of tax liens?

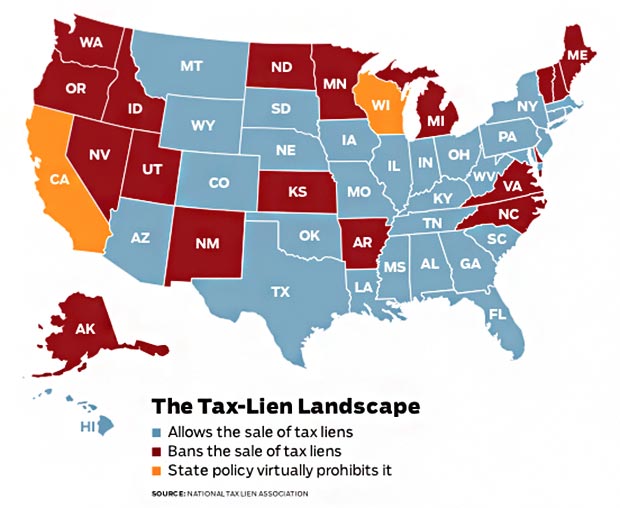

Some local governments opt to sell property “tax liens” to private investors in an attempt to generate short-term cash flow while also reducing immediate public sector staffing costs related to delinquent tax collection. (Tax liens are the debts encumbering a property in the amount of delinquent taxes plus associated interest and penalties).

From AARP Bulletin. Source: National Tax Lien Association

Tax lien sales in different jurisdictions have raised important questions about the prudence and effectiveness of this approach in terms of revenue generation, the return of property to productive use, and concerns about protecting both homeowners and their investments. By selling tax liens for less than the full amount represented by a given lien digest, local governments do not recapture the total value of delinquent taxes.

Moreover, by transferring tax liens and all accompanying enforcement mechanisms to the private market, local governments lose the ability to force a transfer in property ownership through tax foreclosure or otherwise. This loss of local government leverage over vacant, abandoned, and tax delinquent parcels is critically important in cities with weak market demand. In those markets, private investors may not easily be able to sell low-value properties and may choose instead to speculate on future payments of interest and accrued penalties, or they might acquire property simply to hold for passive investment.

In these circumstances, and in any circumstance where the private market holds a tax lien that is valued at more than the fair market value (FMV) of the underlying parcel, the private investor has no business incentive to incur the cost of foreclosing on the parcel or otherwise forcing a transfer of ownership of the parcel to a responsible owner. Private investors and speculators holding tax liens often take no action on tax liens associated with the lowest value properties. As a result, those properties remain vacant and impose significant costs on the community and on the local government in terms of police, fire, and code enforcement calls. Because the local government gave up its ability to use the tax foreclosure process when the liens were sold, those properties may sit in limbo indefinitely with no clear means to force a return to productive use.

A recent analysis of tax delinquency and collection in Rochester, New York found that the most effective intervention in reducing the negative community impacts of vacant and tax delinquent properties is to force transfer to a more responsible owner. (Community Progress was hired by the City of Rochester to conduct this analysis and to produce a report, Analysis of Bulk Tax Lien Sale: City of Rochester.)

What reforms strengthen tax foreclosure statutes?

An effective, efficient, and equitable tax foreclosure process is an invaluable tool for municipalities in their property acquisition and neighborhood revitalization toolkit. Unfortunately, many states’ tax foreclosure laws compound the negative impacts of delinquent parcels on communities. Why? Because the complete tax foreclosure process takes many years and does not necessarily result in insurable and marketable title at the back end of the process. Reform of property tax foreclosure laws should focus on the following elements:

- Shift to in rem foreclosures. Shift the focus from collecting a personal judgment against the delinquent property owner (in personam) to enforcing a lien against the property (in rem). This foreclosure process requires less burdensome notice than processes seeking to collect against an individual, and can also result in clean title (title that is free from liens or ownership claims) to the property.

- Create judicial tax foreclosure proceedings. A judicially supervised and approved tax foreclosure is more likely to produce insurable title at the end of the tax foreclosure process since it requires a judicial decision guaranteeing constitutionally adequate notice to all parties.

- Provide for constitutionally adequate notice. The United States Constitution requires local governments to give property owners adequate notice before their property can be sold to satisfy delinquent taxes, and the contours of the required notice are described in several Supreme Court decisions, most notably in a 1983 case called Mennonite Bd. Of Missions v. Adams. Because the vast majority of state tax foreclosure statutes were enacted long before the Mennonite decision, most tax enforcement statutes do not require constitutionally adequate or “Mennonite” notice. The resulting lack of constitutionally adequate notice in many foreclosure proceedings is the primary reason why tax-foreclosed properties are considered to have title defects and serious limitations on marketability. States can revise their property tax foreclosure laws and accompanying local systems to ensure compliance with constitutional standards.

- Shorten time periods between delinquency and foreclosure. Multiple years of tax delinquency combined with interest and penalties can result in outstanding tax liens against a given parcel that are greater than the FMV of the property. This is particularly true when the property is vacant and has deteriorated over the period of the delinquency. When tax liens exceed FMV, the property simply will not be transferred on the open market.

- Allow large-volume bulk foreclosures. Judicial in rem foreclosures can be constructed to permit a local government to process hundreds or even thousands of parcels in one short hearing.

- Provide for sales with no required minimum bids at tax sale. State or local laws can be amended to permit either the minimum tax sale bid (the value of all outstanding taxes, interest, penalties and costs) to be reduced to a lower amount, or can require the automatic transfer of some or all tax delinquent property to a public entity, such as a land bank, in order to support public priorities.

- Provide public mechanisms for forgiving or waiving delinquent taxes. Providing through state or local law mechanisms for public entities to forgive or waive delinquent taxes on vacant, abandoned, and substandard properties can be a powerful tool in returning property to productive use.

It’s important to recognize that there may be homeowners who are struggling to pay their taxes. Although a good delinquent tax enforcement system allows numerous opportunities for an owner to pay their taxes, the most critical intervention point to help these homeowners is before their property becomes part of the delinquent enforcement process. Municipalities should have multiple ways to identify and assist these individuals. If early warning systems and assistance programs do not exist, municipalities should develop them.

(Portions of this post were taken from Land Banks and Land Banking (2011), by Frank Alexander for the Center for Community Progress.)

Subscribe to join 14,000 community development leaders getting the latest resources from top experts on vacant property revitalization.